Stacking Functions Part 1 – Pawpaw Perfection  “Stacking Functions” – we hear the phrase all of the time in the Permaculture world, but what does it really mean? Is it simply another variation of “two birds with one stone”? It can be used that way, but at it’s best, stacking functions really is a system-wide philosophy. We look at overall needs on our site and match inputs and outputs in mutually beneficial ways. Over the next few months, I’m going to take you all on a tour of some different designs with awesome and creative function stacking, starting with a design I’m really proud of on my own site. It began with observations about 3 different elements in our system. But first, a little background on PawPaws. The Pawpaw is the largest native North American fruit, with loads of benefits to enjoy. In late summer it produces clusters of a delicious, creamy fruit, it’s shade tolerant, browse resistant, a butterfly host plant and can handle wet feet. It’s a great tree to plug into those dark corners of the property that you’re looking at and thinking.. what can I put there?? It is flowering now (mid-April), and the flowers are small and dark red, hanging upside down from nearly naked branches as the leaves begin to emerge. A small, resilient tree that produces heavy yields, it's perfect for the homestead. Now that we know the basics, on to our observations. 1). We have a challenge on our site, and it’s of our own making. We process thousands of poultry animals here every year – chickens, turkeys, and ducks. The water coming out of our outdoor poultry processing facility is full of Nitrogen and nutrients and flows downhill toward a pond on our property that overflows into a crick that feeds into Raccoon Creek, then the Rivanna, then the James, and on out into the Chesapeake Bay. We don’t want to send all of this extra nutrient into that system so we need a creative solution. 2). One of our small business enterprises is oyster mushroom production. We’ve frequently got a lot of “spent” mushroom substrate (most often a sawdust and/or grain base/mixture) that is no longer useful in commercial mushroom production, but still has a lot of life left in it to grow and spread. During our last PDC course, Eli Talbert of Talbert mushrooms was giving a guest lecture and said something that caught my interest. “Mushrooms are just Nitrogen gobblers. Especially oysters, they’ll eat almost anything”. I knew this in principle, but a new lightbulb came on in my head. 3). We have a love of Pawpaws, and are starting to work towards propagating them. We purchased 20 bare root trees this winter to start a pawpaw patch that we can later graft desirable varieties onto. This way we’ll grow the top notch varieties and produce our own scion wood (mini function stacking) so that we can propagate specific cultivars. With these observations we were able to creatively meet a need, reduce our waste, and increase our abundance. Here’s how: We dug a series of swales going down our hillside next to the processing plant and are in the process of filling them with wood chips to act as a sponge and filter. There are 4 of them so far, and we intend to add more this summer and extend the system further downhill. The top swale catches the runoff from processing at its Easternmost end, and it’s dug at a very gentle grade so the water moves downhill to the spillover point at the Westernmost end. The spillover carries the water to the next swale where it enters on the West end and flows gently downhill to the East, where there’s another spillover, and so on. In this way, the water zig zags slowly downhill through these swales and has a lot of time and space to be absorbed and filtered before entering our watershed. But here’s where it gets cool. Pawpaw flowers have this really cool strategy for reproduction. They have the dark red, veined appearance of raw meat. And they stink! They smell of decay, some even say they smell like rotting flesh. These two characteristics attract carrion flies, which are the pawpaw trees’ pollinators. And guess what enterprise on our farm attracts carrion flies? Poultry processing! Our composting poultry “leftovers” (any guts we can’t use, feathers, skin from peeling the feet, blood etc.) always attract flies, and we’ve located those piles at the top of the swaled. Aaaand, Pawpaws can handle wet feet. They won’t mind being planted in a place that gets periodic heavy wettings (processing days use a lot of water). Pawpaws also have a deep taproot which will help stabilize the berms on which they’re planted.

And here’s where it gets cooler. Whenever we have leftover mushroom substrate, we just throw it on top of the wood chips in the swales and let the mycelium “run”. Those oysters can gobble up all of that rich Nitrogen from our processing days and keep it out of the waterways. We won’t eat those mushrooms, we’ll leave them to keep reproducing. They’ll also help facilitate a fungal network in the soil, which was recently turned over from grass pasture. This will help the survival of the trees which have evolved in forested ecosystems with a healthy fungal community. So our main inputs here are labor and design. It took a lot of work to dig swales (thanks interns and Spring 2019 U of R PDC Students!) and plant the trees, but the harder bit was establishing the design concept. Once established, the outputs are huge! Clean water, nutrient absorption, delicious fruit, fungal communities, making use of the flies on site, swale stabilization, shade, aesthetics, scion production, seed production, pollinator hosting (Pawpaws are a butterfly host tree, in fact zebra tail swallowtail butterfly larvae will only feed on Pawpaws and nothing else) and more. This is just one example of what stacking functions can do when applied on a whole system level in your Permaculture designs. Stay tuned this summer, we’ll take a look at a lot more interesting and inspiring design examples. Enjoy, and go plant a Pawpaw!

1 Comment

Thoughts On An Unexpected Death On The Farm  “When you take responsibility for an animals life, you must also take responsibility for its death” –Emilie Tweardy I didn’t realize how emotionally connected I had become to my pigs until I had to kill one unexpectedly. A few days ago one of the two pigs we’ve been raising for meat was mortally injured and left paralyzed in half of its body, and after consulting with the vet, we decided to euthanize him. It was solemn and shockingly violent, but thankfully it went very quick. First the vet sedated him, and once he was unconscious, I shot him twice between the eyes with my rifle. Later, alone on the farm, I buried him in the ground with a few heartfelt prayers. I know we made the right decision, but it doesn’t make it any less heartbreaking. The worst part was seeing the crippled, feverish pig suffer – that’s when I realized how visceral the bond was that I had developed with him over the past few months. It is a strange, new feeling – not like the grief of losing a pet, there were no tears – but more of a heavy sadness that hangs like a weight from my chest. This is my families first go at pigs, and one of the things my wife and I are reflecting on now is that our pigs have become a familiar comfort to us – a vibrant part of the interconnected living system of our farm. I knew I would have to butcher them soon, and I had always imagined harvesting them with reverence knowing that they would be recycled to nourish my family and friends. Now I’ve lost that meaning for this pig and I am struggling to make sense of it. He will feed the soil food web now and next season we will plant a mulberry tree over his grave that someday will feed another generation of pigs. Still, something feels wrong and I have to sit with that for now.

I think I’ve already recognized some lessons from all of this. One is to always have an on-farm plan to butcher in emergencies so the meat can be salvaged. Another is to raise a more resilient breed (it seems like this particular injury is common in Mangalistas). There is an idea I’ve heard that industrial-scale agriculture fosters a society that becomes inured to violence, and that might be true to an extent. But then it must also be true that the experience of raising animals, working alongside of them, and taking responsibility for both their lives and their deaths, makes us take violence more seriously. I know that it has for me. Beyond Meat – Tapping Into Additional Yields From Animals On The Farm  I farm because I desire that raw tangible connection to nature, in essence to ourselves. I also farm because I enjoy producing food that we eat, it makes me feel safe and eating food from the land we work with every day deepens the connection that satisfies my soul. We produce a variety of things on our farm, but the biggest contribution to our own diet is meat. We easily provide ourselves with all the meat we need. Our meat consists of goat, chicken, beef, and the occasional wild caught deer and even groundhog. Not only are animals a part of our farm because they provide us with food and income, but also because we enjoy being around and interacting with them and I feel that our life is richer for it. They teach us a lot about communication and intelligence and patience. By raising the animals we eat we can also be sure that they are treated humanely, live a good life, and that their dispatch is performed with respect and is quick and as low stress as possible. In addition to the meat for our table, animals provide a plethora of additional yields. Over the past few years I’ve been dabbling with these additional yields, learning how to process different parts and how to enjoy and utilize what they produce. These are some of the ways we tap into the additional yields that our animals provide. Needless to say, nothing on our farm dies in vain. Once the meat is cut from the carcass, the bones are boiled down for a nutrient rich broth which is frozen or canned for future use. I add vinegar to help pull the minerals from the bones into the broth and let it cook for 12-24 hours before straining the bones out. Beyond just using broth as a soup base, it’s a wonderful rich substitute for water when cooking rice, greens, or beans. Animal skins are an amazing resource. Early on, I filled our freezer with beautiful skins that I couldn’t bear to toss out until I taught myself to tan them (with the help of books, articles, youtube, and trial and error). Tanned animal skins can be made into clothes, bags, blankets, or even just used as home decor with a deep story. I took a 3 day workshop to learn how to make buckskin (the soft supple suede like leather with no hair) – using the brains of the animal, lots of elbow grease, and smoke. And although I haven’t made anything with my buckskins yet, a skirt is in my very near future. After learning to tan hides for myself I began to offer my services to local hunters who wished to preserve the pelts of their kills. Tanning for others is now a way I bring in a bit of extra income during the winter in the ‘off’ season for the farm. Animal skins can also be made into rawhide. Rawhide is skin that has simply had the hair taken off and then dried. I’ve salvaged deer hides that would’ve otherwise been tossed from local hunters and made them into beautiful sounding drums by stretching and tying them over hollow forms. Rawhide can also be cut into a thin strip and used as strong lashing. Fat is rendered down into lard for cooking. Rendering is as easy as cutting pieces of rich white fat from the carcass and melting them down in a pan or crockpot. The fat is then strained into jars while it is still hot and in liquid form and then cooled and used for cooking throughout the year. Lard from our goats has become a staple in our kitchen for cooking and it also keeps our cast iron cookware, which we use on a daily basis, well-seasoned. Lard can also be collected from the top of a pan of fatty broth where it rises and solidifies once it is cooled in the refrigerator. Lard can also be used for making soap (with the other main ingredient being lye). I’ve made soap from hog lard in the past. I’ve even collected the fat that is scraped from bear hides in preparation for tanning them for hunters. Now while I wouldn’t use this for cooking since the skin it is scraped from is fairly dirty, I render it the same way and we use the resulting grease as a boot oil and conditioner for metal tools. I even used it once to get pine sap out of my hair!! Hooves from goat and deer are removed and make a lovely sounding rattle to play along with the rawhide drum. The feet from chicken can be eaten or used with the bones to make broth, but we mostly dehydrate them and utilize them as nutritious dog treats. Anything that isn’t utilized is composted and returned to the earth from which it came. To follow Betsy and her work at Peacemeal Farm check her out on Facebook at

https://www.facebook.com/PeacemealFarmVA/ Permaculture And Faith  I stumbled upon permaculture by accident in 2012. At the time, we were living on ten acres of land in Nelson County and had decided to revisit the task of growing a garden and raising our own animals. Having been raised on a dairy farm in Northern New Mexico, I had been immersed in all things farming and gardening. Hard work was the motto. The art of self-sufficiency was our way of life and, with a mother raised in the Mennonite faith and tradition, she was a master at growing a large garden and canning/preserving food. To this day, I can still hear the canners rattling and hissing away as yet another batch of tomatoes and green beans were put up for the harsh Rocky Mountain winter ahead. Years later, as our family settled on our own piece of land, I realized that farming and growing things had never really left my blood. It was like my fingers itched to get into the soil as soon as March and warm spring days hit our patch of grass. However, unlike the rich soil of our tiny, New Mexico town, the soil we encountered was clothes-staining red. It was so heavy with clay that we were at a loss as to how to plant in this new place. We were attempting to successfully raise food on land that had only seen a passing herd of cows. Somehow, we needed a new approach. Enter permaculture. Through our initial study of permaculture, we quickly figured out that the incorporation of sheet-mulching and organic leaf material from the woods nearby could quickly increase the soil’s fertility to then grow things quite successfully. Permaculture was a whole new way of thinking that took the traditional way of gardening I was raised with and made it a richer, deeper experience.  I can tell you that there was nothing quite like harvesting our garden that first year. While it was far from a perfect harvest, the fact that we could take a previously unyielding landscape, and see it produce bountifully, was exhilarating. However, the piece that I was not expecting, was how much the practice of permaculture resonated so deeply with my own personal faith practice. As I read more about the 3 ethical pillars of permaculture - the call to Care for the Earth, Care for People and the practice of Fair Share - I was reminded of this Biblical passage from Genesis 1:28; “And God blessed them. And God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over every living thing that moves on the earth.” As a young girl, I was raised in church with the belief that this creation we see and experience each day has a Creator; a Creator who I could have a personal relationship with and experience, not only through faith, but also through interaction with the world around me. However, as I grew and studied Scripture for myself, I began to understand that part of that relationship with my Creator was to answer the mandate given in Genesis to care for the earth, people, and animals He had created. In fact, if you’re a student of the Biblical text, you will find other passages that point to this call to care for the earth and God’s people throughout Scripture. I’ll be honest and admit that we as a people of faith have not always heeded that call and the ramifications of that neglect are seen in our world today. However, for me to wait on someone else to step up to do what I feel God is saying in my life, is not to live out an active faith, but rather a disobedient one. I embrace the practice of permaculture because I feel it best expresses how I am called to care for the Earth and the people that make up my community and beyond. It is through the practice of permaculture that I feel I can authentically work in harmony with creation and the patterns of nature set forth from the beginning.

As a young girl, I spent enough time outdoors to see those patterns of nature emerge in everything we did on the farm. The coming of new, Spring calves and watching the way a garden grows - from seed to greening plant - with the help of care, water, and sun. It is when we honor these cycles of nature and how they work with one another that we have the opportunity - dare I say privilege - to enrich and heal the land instead of robbing life from it. However, just as much as permaculture and my faith is about the care of the earth, it is more importantly an opportunity for me to care for people in my life well. Throughout the last 16 years of being a business owner and employer, I have seen how my own practice and understanding of permaculture has impacted the company I own and lead on a daily basis. We are a company that builds things but, more importantly, we strive to build-up people. By focusing on building people through job placement, skill acquisitions, and care for one another as a work community, I also answer the call of caring for people through the lense of my faith. It matters how we treat people, receive them, and choose to care for them beyond just a paycheck. If I truly believe that each person is uniquely created and has infinite worth, then my faith calls me to care for them well by building-up and serving the community God has put in my particular sphere of influence. As I reflect on all I have learned through the last few years of studying permaculture, this quote from the Scotsman, John Muir, sums it up well for me; “Oh, these vast, calm, measureless mountain days, days in whose light everything seems equally divine, [that open] a thousand windows to show us God.” May I forever look through the windows of creation to its Creator as I hike the bounty of the Blue Ridge Mountains; as I bend to press my hands into the soil of this valley I call home and care for the people within my greater community. Rope A Dope Style - A Case Study In Creative Use and Response To Change How many of y’all hear Gerald Levert looping in your head right now behind that title? Or have visions of the Mayweather vs Mcgregor fight last year? As a 90’s kid with an appreciation for combat sports, I could say a whole lot about both. But this blog is not a nostalgic ride through my childhood, it’s about permaculture and farming. And farming is a blood sport. Why then the Rope A Dope? For those not familiar with the Rope A Dope concept, it comes out of the boxing tradition. The Rope A Dope was made famous by Ali. At its simplest, it is a strategy in boxing where the boxer appears weak, by doing so, invites his opponent to fire off a flurry of ineffective punches. The boxer is on the ropes, which allows the rope to absorb the shock of the punch. In this scenario it appears as though the boxer is being beaten badly, only to turn the fight in their favor quickly at the right moment with a well-placed blow on a tired opponent. Ali beat Foreman (a heavily favored opponent) with this strategy. The fight is up on youtube - every time I watch it I get goosebumps. In permaculture, we often find ourselves in systems where we are over matched. I’m on the ropes. For the last decade, I’ve been vegetable farming at the market scale. I started out building a not for profit farm and then transitioned to build my own small farm. I have learned much. The seasons on an intensive small scale vegetable operation are long, brutal, and rewarding. Revenue can be extensive, but profit, in the early years especially - is sparse. It’s not uncommon to watch the thin margin on the season disappear in one night in a clandestine orgiastic Roman style feast at the hands of the local whistle pig community (that’s groundhogs for those not from the valley). Excess consumption is not unique to the human sector. I have come to love hunting the beasts down with a crossbow, literally counting the dollars saved with each kill. Photo from left to right: the farm a decade ago, an overhead of the farm now, a picture of the lower field that is now flooded. Some seasons are difficult,

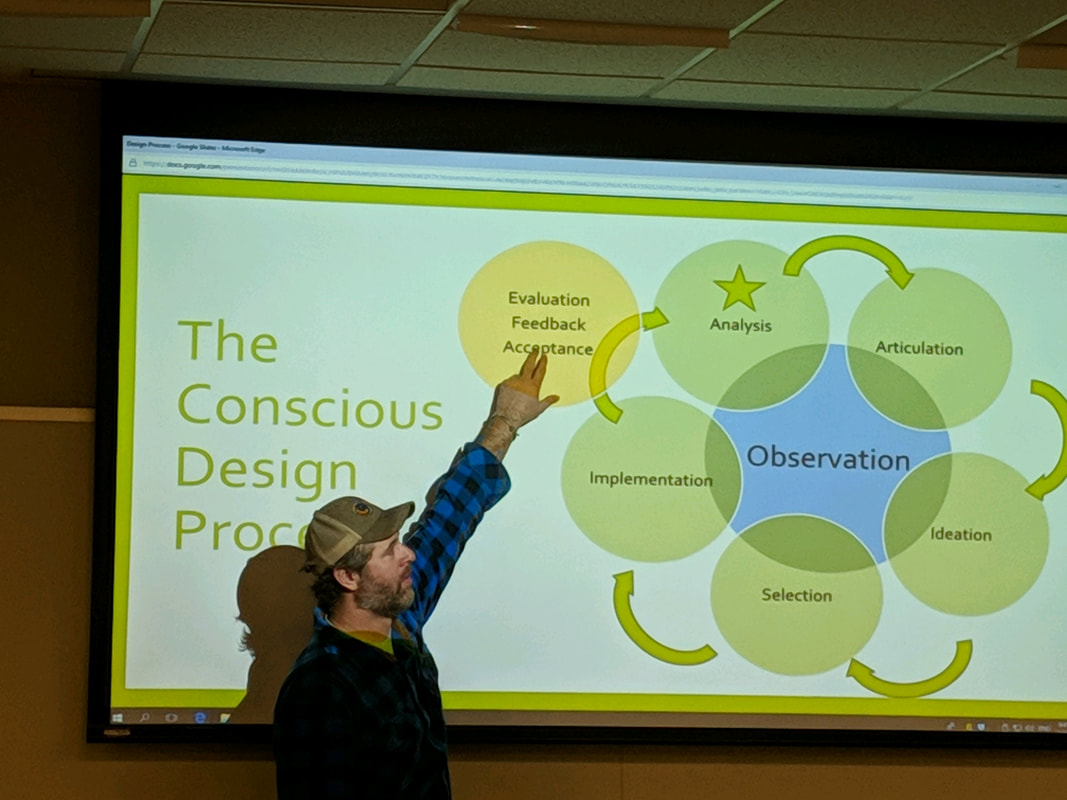

Some seasons will sink you. We live in a valley, peppered with microclimates. Last year, in my corner of my county, my site received almost 80 inches of rain. We average 36 inches a year. In all of my design work on the site, I never imagined this much water. The perennial systems performed well, but the annual systems, on which I depend for income, failed. By July, my neighbor’s property sprung a spring, and a creek developed that ran across my driveway into my lower fields. 9 months later as I’m writing this, there is still water running across my driveway. And my lower field has been underwater since last summer. Feedback, not failure. What do I do? I could lease extra land off-farm, and push forward through the barriers refusing to change the direction I set ten years ago. This would require pouring more resources, human calories, gasoline, infrastructure - money - into keeping the dream alive. Instead, I lean on my training. In permaculture, we look at the goals of a project, our ethics, and the 12 principles to evaluate a design. In the middle of this crisis, both existential and financial, the two principles that provided the most relevant support in our evaluation were; obtain a yield and creatively use and respond to change. We asked ourselves the questions, what are our goals? What are our yields? Our goals point towards connection, sustainability, and financial stability. The vegetable operation isn’t cutting it. After years of pushing sometimes 60 hours a week, I am 40 years old, broke and facing an effort to salvage an unsustainable project. This cold analysis is hard. Permaculture is not for the brittle spirit. But, it is freeing. My next step is to point positive. What do I have? I have a killer homestead. Professional grade paid-for infrastructure, tools, and equipment and deep knowledge of plant systems - I have my formal training in counseling, deep roots in a community that I am native to, and passion for medicinal and useful perennials. By focusing on what I have, rather than what I’ve lost. By applying my assets to goals of the project plus hard climate realities I am able to move forward. What it looks like. It’s time to stop the vegetable hustle. My site is no longer appropriate for it, nor my familial context. I am in the midst of pivoting toward a more perennial system and utilizing my present infrastructure to grow out and produce medicinal and edible landscaping nursery stock. In addition, I can lean on my formal training as a mental health counselor to find off-farm work that supports resilience in human sectors in my community and my family. Psychologically, this moment creates an opportunity to re-brand. Our new name is Moonstone Plant Company. Zora Neale Hurston - the anthropologist and writer once described strength as like being a rock or a blade of grass. The rock is hard but worn down and broken by water, whereas the blade of grass is unfazed and yielding - strong - when confronted by the elements. (Students of Taoism/Ch’an Buddhism may recognize this idea. I love the thought of Hurston reading Lao Tzu.) In permaculture, we can’t be hard rocks, breaking ourselves against uncontrollable sectors. At the end of the day, rather than moving forward stubbornly only to crumble like last Christmas’ peanut brittle, turn to permaculture principles, ethics, and the design process as the structure for a thoughtful, relaxed, and flowing decision making process. This is the seat of resilience. We must change. When you find your project at this moment do three things.

Small price - big yield Find the leverage point in the system. Projects stumble - shit goes sour, just remember the Rope -A- Dope.

|

Authors

Daniel Firth Griffith Archives

June 2022

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed