|

We've got a big announcement, and it's one we're really excited about! It's a really cool story that begins with the Permaculture Ethics.

On day one of each Permaculture course, we cover History, Ethics and Principles. The 3 Permaculture Ethics, and the backbone of all we do in this field, are: Earth Care, People Care, and Fair Share. A few years ago, on a muggy September Friday morning, when we began our course with these lessons, one of our students found themself in the middle of a transformative experience. The mixture of being immersed in a group of like-minded learners, combined with encountering the ethics and principles of Permaculture made a strong impression. This student was hungry to continue to plant seeds (both metaphorically and in reality) for their future as well as their community's. They were also wondering how to give back. What did 'fair share' mean for them? The alumni thought, "How can I help engage others in this work?" They had a proposal. They approached us with the generous offer to anonymously donate full tuition for 1 student for each of our next 10 courses. That's 1 full-ride scholarship for each PDC over the next 5 years! What a great way to give back to their community, improve access to the material, and live the ethics! We are so humbled and inspired by this offering. Our donor has dubbed this "The SPI Scholarship", SPI in this case standing for "Seed, Propagate, Initiate". They hope that their donation will help in planting the Seeds of Permaculture in individuals that will then Propagate the knowledge and Initiate future projects and connections throughout the ever-expanding community. What an incredible vision! See the course registration page(s) for details on how to apply for this scholarship.

1 Comment

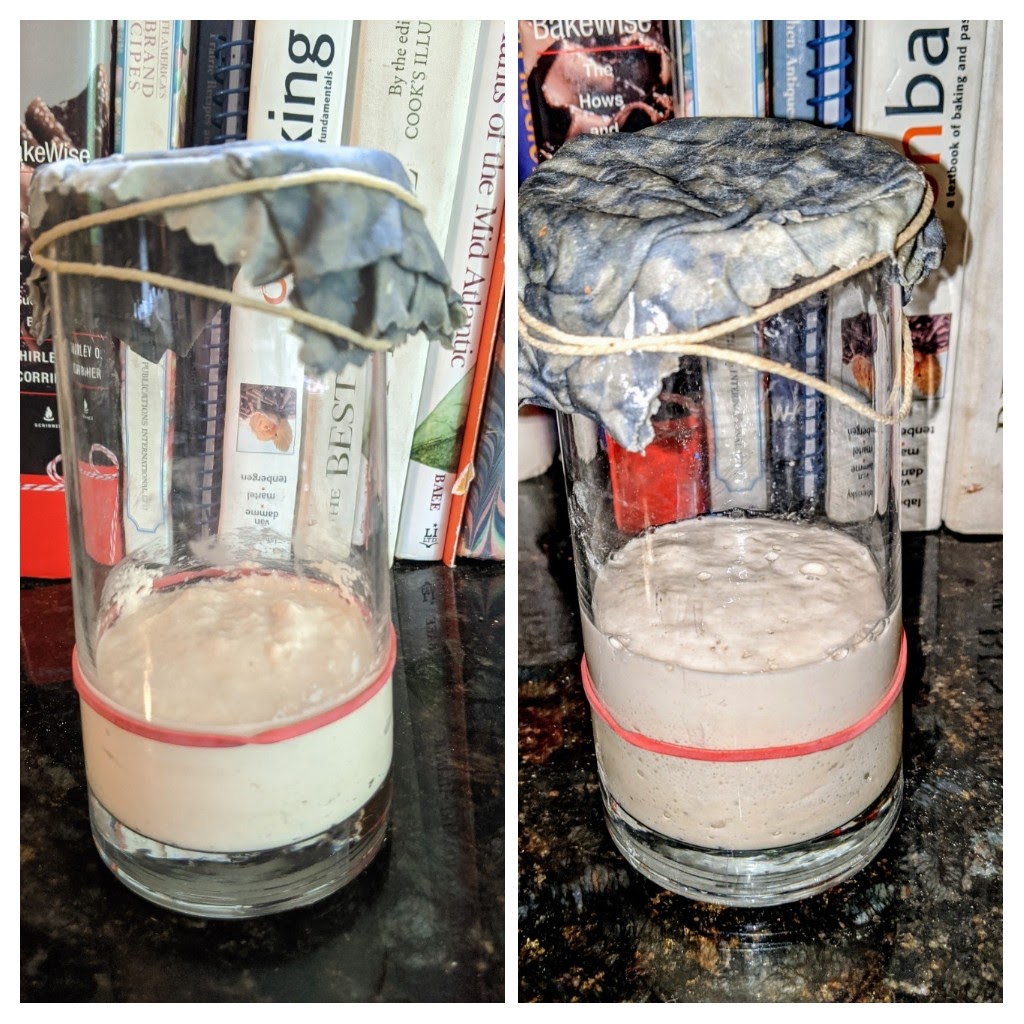

Sourdough is having a (another) moment. More people than ever are baking with a starter, yet commercial yeast is scarce. I hear lots of folks saying that they can’t find yeast anywhere when the truth is, yeast is EVERYWHERE - and it’s really easy to make this abundant resource work for you if you just follow a few simple steps.I made a starter years ago using the King Arthur method and I’ve baked with it several times a week ever since. Here is the super simple method for creating and maintaining your own sourdough starter: Step 1: Combine about 1 cup of whole grain flour and with ½ cup of warm (not hot) water. Let it sit, covered with a kitchen towel for 24 hours. Make sure you start with some ground, whole grain flour. This can be rye or whole wheat. There is much more natural yeast on whole, unprocessed grains. Step 2: Mix ½ cup of the mixture with 1 cup of all purpose or bread flour and ½ cup of warm (not hot) water. Let it sit at room temperature, covered with a kitchen towel for 24 hours. Only using ½ a cup of the mixture during the initial feedings create a lot of “discard”. I don’t believe in discarding ingredients so I’ll include some ideas for using the discard at the end of this post. Step 3: Mix ½ cup of the mixture with a cup of flour and ½ cup warm (not hot) water. Let it sit at room temperature, covered with a kitchen towel for 12 hours. Every 12 hours is a target but you don’t have to be exact. I’ve had lots of people tell me that they let their starters keep them up at night wondering if they remembered to feed them. Don’t stress. These things are difficult to kill. Step 4: Repeat step 3 every 12 hours until the starter bubbles and doubles in volume during the 12 hour resting period. This could take anywhere from 1 day to over a week. There are plenty of variables involved - from the temperature of your kitchen to the amount of yeast and bacteria in your grain and in the air. Don’t stress. Almost everyone thinks they’ve done something wrong at this point. Nope, you’re fine - even if you don’t see any activity at all. Keep feeding, it will happen. Step 5: Use and maintain your starter. I keep mine in the fridge and feed it whenever I bake, or at least once a week. I use a scale to add 50 grams of flour and 50 grams of water per feeding and I never discard any starter. That’s it! Like I said, it’s super easy. This is ONE way to make a starter and there are tons of other methods. Some people use different kinds of fruit, grains, and so on. I keep mine strictly grain and water and it works really well for me. Experiment and have fun! I’ve included a few tips below. Why Sourdough In my opinion, sourdough starter is superior to commercial yeast for at least three reasons:

Discard uses Create no waste, value the marginal, obtain a yield! You can do so many things with the “discard.” You can add it to quickbread recipes, make sourdough pancakes, dumplings, crackers and more! These recipes are easily found online. It’s been a long time since I created any discard so I don’t have recipes that I use per se. You can save it up, keeping it in the fridge to use all at once or spread it out into different recipes as you create your starter. Remember, you really don’t need to throw anything away once you have a starter created. Just keep your starter in the fridge, bake once a week at least, and replace what you take by feeding the starter. Pre Fermenting starter before using Before I add starter to a recipe I pre ferment some. This is sometimes referred to as “fed” starter. I simply add 1 part starter, 1 part flour, and 1 part water together and let it sit at room temperature until it starts to bubble. About 1 hour. Converting recipes to use sourdough My go to formula for converting a yeast based recipe to a sourdough recipe is as follows: Add about 20%, by weight, starter to flour weight. So if you use 500 grams of flour in your recipe, use 100 grams of fed starter (see above under “pre fermenting.” I also subtract liquid and flour from the recipe in relation to the amount of starter. So if I use 100 grams of starter, I reduce the flour and the liquid in the original recipe by 50 grams each. Which is why I keep my starter at 100% hydration. Make sure to ferment your doughs longer than the commercial yeast recipe calls for - typically at least 4 hours. Why 100% hydration I feed my starter to maintain 100% hydration, meaning it has an equal ratio of flour to water, by weight. This way it is easy to know how much of each flour and water I am adding to any given recipe and the starter itself has no effect on the hydration level of my sourdough bread formulas, no matter how much I choose to use. Why Change the Amount of Starter in a recipe? Counterintuitively, the less starter used in a recipe, the more sour the bread will be. This is because it takes longer to rise, and therefore it ferments longer, creating a more sour taste. Don’t Fear the Hooch That water that comes to the surface of your starter, it’s no problem at all. It just means that your starter is hungry. Feed it. You can either pour it off or stir it right in while you’re feeding your starter. Drying starter As an insurance policy, you can spread some starter as thin as you can onto some parchment or a silicone baking mat and let it air dry for a day or so, until it’s brittle. Then just break it into pieces and store it in an airtight container in a cool dry place for up to a year. You can rehydrate it with a tiny amount of water and then feed it as normal. This can be used to “take a break” from baking or in case something happens to your starter. Several years ago I kept my starter in a glass container and it was somehow broken. I couldn’t salvage any of it for fear of having glass shards mix in. I WISH I’d had some dehydrated starter to rehydrate, but I didn’t. Once bitten, twice shy.  “When we think about sustainability in this business, what we need to think about is, ‘would we do that all over again?’” - Bev Eggleston I recently spoke to a producer and entrepreneur who helped me think about how I want to run my farm. In small Ag., we often throw around words like, ’sustainable’, ‘resilient’, and ‘regenerative’. Typically, we’re referring to Permaculture Ethic #1 – Earth Care (#s 2 and 3 being “People Care” and “Fair Share”). We’re usually scrambling in this era of destruction, deforestation, and destabilization to re-center our works around what is best for the Earth, and thus the future. But, what many of us are experiencing right now is a good hard look at whether or not our lifestyle itself is sustainable. Cut off from much of our socialization, many of the instant gratifications of our familiar forms of consumerism (“you mean my Amazon order will take 6 whole days to get here???”), our places of work, play, and worship, we are faced with the need to distill our lives into something that can not just sustain us, but can sustain over time. For many, this respite from taking 3 kids to 5 overlapping sports seasons while working full time across town and hitting the gym 4 days a week is a welcome break - a forced stillness and reflection that have so many of us wondering if we can ever go back to life as it was, whether that means slowing down, connecting more, or changing things altogether. So, I’m enstating something I’m calling, “the do-over test”. As I’m pondering the meaning of sustainability for me, my farm, or my family, I’m thinking, “OK, if we had a do-over on what just happened, would we do it all just the same? And if not, what would be different?” Let me back up a moment. My husband and I own and operate ShireFolk Farm, a small, diversified farm in rural Virginia in the general neighborhoods of Richmond and Charlottesville. One of our main enterprises is pastured poultry, particularly chicken. We recently processed (butchered and packaged) our first batch of the year, about 230 birds. We do this on-farm, entirely on our own, under a federal exemption that allows us to process (perfectly hygienically, mind you) in the open air of the great outdoors. We spent two and a half days sending our 230 beautiful Freedom Ranger chickens to “freezer camp”. On the heels of 2 other very physically demanding weeks, and after 20+ hours of standing on the drained concrete slab where we do our work, (using our bodies in repetitive motion to perform tedious, skilled labor) we were worn out.

When you eviscerate a chicken, you use wrist and hand muscles only climbers and concert pianists are familiar with. You begin to feel long-lasting aches and strains in the sinews of your wrists, in between your knuckles, and right down deep in the meat of your hands. It’s a strange feeling. On top of this, I’m currently about 4 months pregnant and the pregnancy hormone Relaxin that’s flowing through my system is loosening everything up in strange ways, making my bodies’ support system a lot more, well, relaxed. So at the end of all this I was feeling footsore, achey, and very much done. And this was only the first processing cycle of the year - we’ve got at least 8 more to go! I thought maybe I was the only one feeling it, but it turns out the rest of the team was feeling the drag just as much. And it got us all feeling pretty down. Nothing was different from former years, we had the same number of experienced hired hands, processed the same number of birds, and nothing went badly. It was actually a very efficient processing. It just suddenly hit us after 5 years of processing our own chicken – we don’t actually want to do this any more. Oh shit. What does that even mean? Back to present moment. We have amazing chicken, I have to say. I have no qualms with our product, and we can’t produce enough of it to satisfy our customers’ needs. But at what cost to ourselves? When we looked back at our processing week and asked ourselves, “Would we do that all over again?” there was a distinct pause. “Will we do that again?” Yes, we’ve got to. We’ve got hundreds of birds on pasture, heading for their eventual destinies in the freezer. But will we do it the same? And do we actually want to do it at all? Maybe not. The gentleman whose conversation I quoteded at the open of this musing, Bev Eggleston, owns a processing plant and sustainable foods marketplace in Northern VA called EcoFriendly Foods. We may send some of our chickens his way, which would mean a total revamp and recalculation of how we do business. How do we cut costs and modify our process to account for the significantly increased cost of outsourcing processing? It’s a puzzle. Alternatively, what if we hired more hands or raised less birds? Either of these options present problems. Hiring in a state of quarantine is tough, and the work requires considerable expertise. Unless we find workers who can commit to a full season’s worth of processing, the return on the investment is minimal because of the time spent getting newbies up to speed. So that’s just more effort on our part, which is the thing we’re trying to minimize. As far as raising less birds, it’s certainly an option, but we’re already sold out of chicken now and it’s a huge chunk of our income as a farm, so we really need to scale up, not down. And what about the simple concern of outsourcing something very dear to us? Will we be less resilient if we depend on others to do this job? We’ve gotten too good at raising delicious chicken and we’ve outgrown our ability to process what we can produce. It’s what we in Permaculture call “feedback, not failure”. Growth is not a failure. But, this feedback means we need to look for new solutions. If we continue on this track we’re headed for certain burnout. As we strive for self-reliance and sustainability here on the farm, we realize we’ve been ignoring the “People Care” ethic, which is an all-too-common mistake for the self-employed. We’re willing to work ourselves considerably harder than what we’d consider appropriate for an employee. We often consider being “overworked” the price of being self-sufficient. There’s so much talk about the supply chain right now that it’s hard not to feel reluctant about outsourcing system elements. Keeping everything in-house feels safer and more certain. But as my colleague Ryan Blosser recently reminded me, “Tediousness is a big factor to psychological sustainability”. And make no mistake, raising and processing chickens is a tedious job. When it comes down to it, the processing itself is simple, it’s the organization and personnel management that we’ve grown tired of. What I like about our potential processing partner, EcoFriendly Foods, is that they are a producer’s group with a processing facility, not a big factory operation. They understand our product and our mission and share our values. This makes me feel good about supporting them and adding them to our network, stacking functions of shared marketing, a new revenue stream and network support along with growth and simplification for our farm. It all leaves me wondering, what else in my life is unsustainable but is so ingrained in my routine that I’m unable to even notice it, much less recognize it for what it is? Are other things grinding me down in a way that I won’t notice until my body or mind is screaming at me to stop? One of our Permaculture Principles tells us to “apply self regulation and accept feedback”. I often talk in class about how this can be the hardest principle because we are not only our own worst critics, but also push ourselves the hardest, despite feedback. The never-ending battle between our mind’s idea of what’s right for us and our environmental or bodily feedback can leave us muddled and confused, trying to balance the two interests. This is where the “acceptance” part of the feedback loop comes into play. We have to listen hard for the feedback, despite our attachments. For our farm, processing our own poultry has always been a real sense of pride, grit, and identity. Yes, it’s hard. Yes, it’s long hours. Yes, it’s something few other farms do (ever notice how few poultry producers there are at your farmer’s markets?), and Yes, we’ve got it down to a science. We are, actually, very good at it. But it turns out, getting good at something doesn’t necessarily make it sustainable. Raise your hand if you’re great at your job. Keep that hand up if you love that work and can see yourself doing it for another 25 years. I feel you. Expertise is not sustainability. This pandemic has showed many of us the weaknesses in our food systems, our medical systems, our social connections and more. It’s forced us to take a hard look at ourselves and our society, and I think one of the silver linings of this might be that personal feedback we can’t ignore. When you’re asking yourself those hard questions, taking those hard looks while you’re waiting on that Amazon order, give things the ‘ol Do-Over Test and see what you find. Would you really do it all the same way again? A resounding “no'' doesn't necessarily mean failure, it means an opportunity for change. In farming, it’s easy to become so dogmatic in our striving for sustainability that we can forget to care for ourselves - which isn’t sustainable at all. In terms of the Permaculture Ethics “Earth Care, People Care, and Fair Share” being a purist about a single ethic will get you nowhere if you’re unable to balance the others. Our Earth Care of raising birds sustainably doesn’t have to mean we can’t adjust our process to give us better People Care. And in this case, we are able to support our local small ag economy further by paying another business to process for us - which means we are doing more “Fair Share” than before. It’s the proverbial bunyip of the ethics, equalizing pressures to find level ground. We’re changing a lot about our farm and our personal lives right now, I think everyone is, and learning to hear and accept feedback from all angles truly is at least half the battle. But as we move forward, we do so grounded by past experience, reminding us where we’re coming from, what our goals are, and what we want the future to look like. I’m so grateful to be working the Earth and connected to my community in this time of change and upheaval, and moving towards practices in our business that we truly want to do over again and again and again.  This morning I planted my hemp seeds - one 50-cell tray the size of a large textbook that will grow enough plant medicine for 20 people for a whole year. My goodness how things have changed since this time last year...and I’m not talking about the coronavirus. I’m talking about the absolutely epic crash and burn of hemp farming in America. A year ago the entire farming community was buzzing with excitement about growing CBD hemp. Every conference I attended, every online message board I was a member of, every casual conversation I had with another farmer - one topic raged like wildfire - the unheard of financial possibilities of the newly legalized CBD hemp market. I’m a new farmer, trying to figure out how to make a living off the land, and a plant geek with a deep appreciation for the cannabis plant, so naturally I dove in head first. I had been forbidden from growing this amazing plant my entire life and now all of a sudden, for a $50 licensing fee, I could grow all I want and potentially make enough money to fund my entire farm for years - hell yeah! I quickly became obsessed with planning my grow - creating a rough business plan, researching growing methods, identifying sources of seeds and plants, etc. A “conservative” estimate of the numbers showed that even if the price of CBD biomass fell by 75 percent, I could still net a profit of about $10,000 off a 1 acre grow. And if it stayed steady…$40,000! At this point in the frenzy it was March, and I hadn’t committed to anything. There was no way in hell I wasn’t gonna do a grow, the question was, how big? Here’s where, looking back, I got lucky in a sense. The excitement and the dollar signs were pushing me to go big. I had grandiose visions of taking out a loan to do a 5 acre grow, busting my ass for a season, and banking $200k - what would be a life changing amount of money to my family. Other people in my network were doing it - some were going as big as 20 or 30 acres. Am I gonna miss out on this once in a lifetime opportunity and regret it later? My instincts said go for it! Fortunately for me and my credit score, my permaculture training kicked in and said, slow down. “Use Small and Slow Solutions” has always been one of the hardest permaculture principles for an impatient go-getter like me to heed. It sounds so trite that it's easy to pass over, but I can’t tell you how many times in my 10 year farming career I’ve looked back on a project and wished I had abided by this simple principle: “Go slow. Grow by chunking. When trying something new, always start with a pilot project”. So somewhere in the middle of all this hemp excitement, I remembered this, and I thought, maybe I should slow down a bit….maybe I should actually listen to that other voice in my head for once. And so I did, sort of…

And hey, I’m not trying to pat myself on the back too much - my instinct was to go big, and it was only my training and history of failure (and the much more level-headed perspective of my wife) that held me back. Kudos to permaculture design and Jenna. So in the end I settled on a half-acre grow - 500 plants - a $3,000 investment. My wife agreed with the plan with the understanding that it was possible that we would lose the whole investment (don’t gamble what you aren’t prepared to lose right?). In retrospect, 500 plants was about 450 more than I should have grown. And that takes me to one year ago - May 2019. My partner and I are furiously prepping beds and building fencing. 300 clones and 200 potted seedlings sit in the nursery ready to be transplanted. We have an incredible amount of work ahead of us, but an incredible amount of enthusiasm too. The plants are beautiful and so are the dollar signs. This is gonna be a wild season! And wild it was. Even with all of the challenges of a first time crop, we grew amazing, healthy plants. The weather was perfect. Our yields and cannabinoid numbers were as good as we had hoped for, and more amazingly, we pulled off the grueling task of harvesting, drying, and processing without a hitch (albeit with lots of sweat and long days). We thought we had done everything right and were ready to reap the rewards... Now, fast forward again to today, May 2020. Every time I log on to social media I see headlines like this one from Politico: “Hemp was supposed to be a boost to farmers. It’s turned out to be a flop.” I haven’t sold one cent worth of product to date. I got lucky - I was able to get my biomass processed into oil and so it is shelf stable, and hopefully I will sell it one day. Most people weren’t as lucky and are still sitting on hundreds of pounds of rotting biomass. Of all the farmers I’ve talked to I only know one who was able to sell his biomass last year. Over 2 months, between July and September 2019, the price of CBD biomass fell from roughly $3.50 a point to $.50 a point. But really, the price fell to zero, because most farmers who didn’t already have good contracts weren’t able to sell it at all. The market was simply way too flooded, and it still is. No one’s talking about hemp any more these days, and the only people left on the message boards are the scammers, people trying to sell used equipment, and that one guy from Vermont who has actually made money off hemp. It’s really depressing. Me, I’m still worn out from the work we put in last fall processing our hemp - damn, it was intense. But I’ve learned so, so much. As I sow the seeds for the 50 plants I will grow this year, I can’t wait to smell those sweet buds again, to watch them turn purple in the frost, to ogle through my jeweler’s loupe at those crystalline worlds of cannabinoid-rich trichomes. Cannabis is a wonderful, multifunctional plant full of soothing medicine. Despite it all, I am incredibly optimistic about integrating it into my diversified, organic operation. But hemp ain’t a unicron y’all, and the thing I realize now is, it never claimed to be. I have a lot of reflections from this last year, but one stands out to me right now (besides a harsh reminder of the unstoppable logic of supply and demand). Somehow in the excitement of the hemp “goldrush” I forgot one of the cardinal rules of small-scale farming - a rule that has been passed down to me by many pioneering small farmers of yore: never grow a commodity; the only way to make money on a small farm is to sell direct to your customers; you have to be a price maker not a price taker. Afterall, I would never even consider growing corn for the open market - I’m not large or mechanized enough to compete. As it turns out I would be better off growing corn than hemp, because at least corn comes with government-backed revenue guarantees! So here I am in 2020. Am I glad I didn’t grow 5 acres last year? Absolutely. Am I still growing hemp this year? Absolutely. I’m learning and adapting like we all are. I am working on a product line of organically grown oils and flowers. I am experimenting with different varieties and different growing methods. One system I am really excited about is intercropping my hemp with my strawberries (the hemp gets transplanted into the field in June right when the strawberries stop producing fruit and the strawberry plants act as a living ground cover for the hemp). I am even dabbling in a little hemp breeding. And all of that, I am doing as small and as slowly as my excitement will allow.  The last cigar I smoked was in a room that I will never see again. It was a Romeo y Julieta and it was insufferable. Although the day was just beginning to cast its shadows, I had already suffered through two exams and twice that number of college lectures. It was past lunchtime and my stomach was mutinous. My pitiable attempts aside, the cigar’s light kept failing, for they require attention and breath and I had neither, for mine were fixed on the room. There are days in a man’s life that, looking back, he wishes he would have showered for; days that, had he known the coming power of that day before its sun rose, he would have donned his best and walked lightly through it. Today, unshowered and ill-shod, I stumbled through one of those days. It was the fall semester of my sophomore year and I had just proposed to my now wife the week prior. The room was Dr. Peter Schramm’s personal library and the cigar was his humidor’s last. Just a number of months before his death, Dr. Schramm had invited me over to his house to discuss my engagement and future plans. We talked of neither. Succession is diversity in motion and the produced stability is sometimes scary. Positioned across from him, our colliding ironies became clear: I was entering life and I believe that he knew he was leaving it. After we sat down and he offered me a glass of whiskey, Dr. Schramm asked if I had ever read any Mary Oliver. I had not, I returned bashfully. To this day I do not know whether this question was measured or impetuous. He loved poetry and everyone at the college knew it. But did he invite me here to read me a poem or talk about the future? It would happen that we did both. With many tens of thousands of books towering over us, he picked up the one that could not have been but fifty pages in length, its insignificant spine impossible for my eyes to locate within his library’s volumes. With untold familiarity, his fingers found the page and opened its text without attention, for his eyes had been permanently fixed on a tree just beyond the windowpane that sat just above his reading chair. A minute went by and then another. To this day I cannot remember the tree’s species; I also cannot remember the color of its autumn leaves. I have tried many times; tried to put myself back in that moment with those eyes. Every time I succeed, however, my soul finds the room and not the tree and I see not the autumn colors but the old man looking out at them. I guess the truth is that, if there is sympathy to be found in this world, look to autumn and be nourished. Perhaps the tree and the man were the same thing, but more on that in a minute. Possibly disturbed by the loud groans of my stomach, the old man finally left his amber colored tree and returned to the room. He was crying. Without an intro or preliminary remark, he read out loud Mary Oliver’s poem, Such Singing in the Wild Branches. This “pure and white moment,” to quote Oliver, changed my life forever. He read, And the sands in the glass stopped For a pure white moment While gravity sprinkled upward Like rain, rising. Dr. Schramm wrote years before this moment that “every poem…contains words we’ve already encountered, but they’re made new because of the way they’re put together.” After finishing Oliver’s poem, he looked at me and said, “Isn’t that new; ‘like rain, rising.’” I think this was the reason he asked me to join him in his library that day. Autumn is poetry and he wanted to share the newness of its bounties. Autumn is a time where the old prepares for the new in seemingly marvel ways; where life may “put together” its tomorrow by losing its today. In many ways, autumn is, “like rain, rising.” And that is perfectly okay. In his seminal work, One Straw Revolution, the “do-nothing” and Japanese farmer Masanobu Fukuoka laments the state of modern agriculture and its dependence on separation and reductionism. It is as if a fool were to stomp on and break the tiles on his roof. Then when it starts to rain and the ceiling begins to rot away, he hastily climbs up to mend the damage, rejoicing in the end that he has accomplished a miraculous solution. Science—this stomping fool—, Fukuoka claimed, “has served only to show how small human knowledge [really] is.” Although one can find serious depth in Fukuoka’s work, perhaps his most piercing argument is his simplest. After a dialogue about returning humanity, its society, and, therefore, its agriculture toward the Great Way—which he defines as “the path of spiritual awareness which involves attentiveness to and care for ordinary activities of daily life”—Fukuoka does what the reader does not expect. He argues for poetry. He contends that modern agriculture’s chemical dependence, tendency toward extreme-erosion and carbon-emittance, and universal health decline is a result of there not being enough “time …for a farmer to write a poem or compose a song.” How can poetry affect agriculture? Perhaps, the better question is what is needed to write a poem? Poetry is the crop of leisure, not haste, and only those not patching their roof in a rainstorm have the ability to write a haiku. Only those who work within the abundant patterns of the natural world have time to reap the harvests of the rain. But poetry is also the commonplace cloaked in the semblance of the new; it is as a tree that casts away its yesterday for the light of tomorrow. Poetry is cigars and windowpanes and tears and death and life. It is the lesson of the library and the old man. It is regeneration, for in its depths we find a version itself. And the poetry of autumn is that the great American Persimmon loses its leaves to produce the leisure filled canvas of the new harvest. Today, on our farm, the summer’s intensity leaves with the chlorophyll and the cooler temperatures bring the joys of calmer days. Chores begin to lessen; management transforms into planning and dreaming; the days grow tired; the rains once again visit the parched landscape; and my soul begins to sink into the hearth. Working with Nature may require everything you have, but in autumn, she requires only patience; she requires only leisure. In autumn, we transform into foragers—into poets—and we have just to wait for the first frost. To forage is to have faith—faith that nature, in all her business and occupation, has not forgotten or neglected you. Perhaps, it is faith that Nature’s patterns and cycles are as constant and rhythmic as they are inclusive and loyal. Either way, Autumn’s welcoming chill shepherds a kingly and favorite forage on our farm: the lush and opulent wild American Persimmon--Diospyros virginiana. J. Russel Smith argued that “the real opening, and great need for the persimmon, is for forage.” Perhaps, the best forage crops are great showmen, for their beauty and mystery capture the eye of the autumn sojourner and beckon his taste's curiosity and wonderment. The show begins in early autumn. It first enters the grand stage by hiding its gumball sized fruits behind its dark and glossy foliage. In mid-autumn, in its attempt to bolster the visual barricade of its lusciousness, its green veil transfigures into a red-hued wall and becomes the ornamental pride of the landscape. Although hogs enjoy the first fruits that drop during this time, it is not until the frost comes and the leaves go that the fruit becomes fit for foraging. Upon exploring Virginia’s interior, Captain John Smith wrote of the new and marvelous Persimmon tree, which “grow[s] as high as a Palmeta; the fruit is like a medlar; it is first green, then yellow and red when it is ripe; if it be not ripe it will draw a man’s mouth awire with much torment; but when it is ripe it is as delicious as an apricock.” Science claims that it is the frost’s bite that drives the tart tannins from its fruits, but I think that, like myself, the tree is simply tired and needs a moment of solace before its autumn harvest—like myself, she requires leisure. Diospyros comes from the Greek root dios, meaning “god,” and pyros, meaning “grain or wheat.” Translated literally, the wild American Persimmon is the “grain of the gods.” Grain in the ancient world was synonymous to life itself—it was the giver of sustenance, the driver of the economy, and the lifeblood of civilization. Although select historians today argue against the direct link between the formation of agriculture and the materialization of civilization, the high nutritional value and storage abilities present in grain production definitively provided ancient man increased leisure in the true sense—“to be free,” or, licere in Latin—and allowed him to drop his guns and pick up a book. The American Persimmon is also very easy to propagate. The best method is feeding it to hogs. The seeds require scarification and the digestion process of omnivorous livestock produce decent results. The hogs get fat and the seeds are prepared for planting. However, there is a cleaner and tastier method that includes saving the seeds after enjoying the fruit and then using the refrigerators as the cold-storage device. Propagation via softwood cuttings are also open to the forager—taken of first year growth and before the first frost—, but this method lacks the fun of hogs and taste of the fruit. The search for freedom is what brings my family into the woods every autumn. We may spend the spring and summer cultivating the land but today we look to the forest to fertilize our soul. On the first frost of autumn, you’ll find our family’s hearth quiet, empty, and cold, for we are lost in the woods and are happily searching for our autumn grain—today, we feel like gods. Foraging for wild American Persimmons in our two hundred-acre forest brings sustenance to our tired souls and lifeblood to our aching bodies. Husbandry is hard, yes, but today, we are foraging and need only patience. Elowyn, our two-year-old and rambunctious daughter, is the best at finding the ripest and most succulent Persimmon fruits. This does not surprise us, however, for only a child can truly see what nature illuminates. The taste of the fruit is equaled only by her joy in finding it. Sometimes, we make a game of it and see who can fill a five-gallon bucket the fastest. Morgan, my wife, is good at this contest and often wins; such is the foraging power of motherhood. On occasion, we neither eat nor collect any fruit at all and find ourselves speechless at the foot of these ornate giants. The wildness of the American Persimmon is also its paradox: if it is the “grain of the gods,” and grain is the product of husbandry, of cultivation, and of partnership, then who is the husband? Let us not forget that even Diospyros virginiana is not self-fertile and its fruiting potential depends on a partner. Perhaps, this is the poetry; perhaps, the American Persimmon remind us of the newness of tomorrow’s life; “like rain, rising.” But I leave this question for you, as I have never tasted a Persimmon fruit; I am highly allergic. Written by: Daniel Firth Griffith,

Owner, Timshel Permaculture & Founder, The Robinia Institute  Homeschool My Kids? No Thanks! While I’ve always admired folks who homeschool their kids and often wondered in amazement how they juggle working, household chores, and teaching their children: we are NOT a homeschool family. I have four very different kids ranging in ages from 5 to 11. Clare, my brainy 11 year old is a self-starter who loves to read and could lock herself in her room for hours, diving into a book series or simply thinking. Eliza, my uber creative and theatrical 9 year old needs to be prodded every 10 seconds or so in order to stay on track when it comes to academic work. Emily, my big hearted 7 year old has an individualized education plan that includes a special education reading and writing teacher as well as speech, physical and occupational therapists. And then there’s Jude, who just turned 5 and loves nothing more than digging a hole, filling it with water and hopping in naked to coat himself and everything around him in mud. So when the Governor announced that the school year was over and that parents would be homeschooling their children (with lots of support from their teachers, thankfully) I panicked. I wondered how I was going to juggle all of the things I needed to get done with all of these kids around the house all day long, not to mention having to take hours out of my day to individually teach these four extremely different kids. Then I remembered that as someone who feels a deep connection to the principles and ethics of permaculture, I’ve been training for this. The way I see it, it doesn't matter if you’re new to the concept of permaculture or you studied directly under Mollison and Holmgren; folks interested in self-sufficiency have been mentally and physically preparing to take care of our families and communities long before this pandemic. We understand how to use and value the resources around us and how to create systems wherein each element has multiple functions. We have the desire and enough know-how to make the best of this situation. In fact, it can be more than that - it can be a bonding time that is full of fun and leaves us with amazing memories.  Meeting The Kids Where They Are While Continuing My Own Chores I was mentally planning my day during my morning cardio as I typically do. I needed to get some more seeds germinating and tend to the gardens - asparagus was coming in and I needed to clean out some beds. I was trying to make a game plan that included both my chores and delivering the kids lessons, and it dawned on me: I’ll have the kids build a children’s garden! They could all get involved (eventually they did). Clare would design the overall space and be in charge of the “budget”. Eliza would research companion planting, beneficial attractor plants, nitrogen fixers, and so on. Emily would read plant name letters to Eliza as she painted some identification signs. And Jude - he would count and plant seeds and dig in the dirt - his favorite thing in the whole world. This line of thinking, where I would create lessons out of the ordinary work that still needed to get done, opened up a whole new realm of possibilities for our homeschool adventure: I would turn normal chores into lessons. There are so many ways to incorporate lessons into everyday life but since I’m a professional chef as well as someone who has to cook for 6 people several times a day, I’ll share how I do this while preparing our family meals. We’re going on week five of homeschooling and sheltering in place and this is working out so far because of one important parameter: I’m meeting the kids where they are while pushing them beyond their comfort just a little each day. Shelter In Place Cooking There are so many lessons hidden within making a family meal: math, science, skill building, art, community building and much more. The whole family can get involved and learn from each meal but there is one caveat and it’s a hard one for me: you have to let go of some of the control. Skill building The most obvious lessons within cooking with kids are the actual cooking skills they learn. My extended family and friends are often shocked to see pictures of my young children using sharp knives. I’ve gotten subtle comments about how “brave” I am (that’s one word for it!) as well as not so subtle tongue lashings about how unsafe it is to have kids use knives. It’s actually quite the opposite: I teach my kids at a very young age how to use a sharp kitchen knife and I would argue that they handle knives, and more importantly their non-knife-holding hand, better than most adults. The secrets are making sure they understand the consequences of mishandling the task and watching and correcting them firmly the first several times. Then, once they consistently handle the knives correctly, I let them know that I trust them to do the right thing. My kids respond well to high expectations: they do better and more careful work when I praise them than they do when I loom over their every move. The hard skills they learn in the kitchen will follow them throughout their lives and include baking, sauteing, steaming, braising, roasting, knife skills, blanching and shocking, and on and on and on. And most importantly, they are highly likely to taste new and different foods that they help prepare. Just last night, my oldest two daughters gave Whitney and I a date night. They cooked us pasta and served it with salad and fruit and they even made us fresh whipped cream with blueberries, mint, citrus zest, and several edible flowers! Math Fractions and relative proportions Homeschool math sounds equally dull for students and the teacher. So why not make it fun with food? We’ve all been there; we’re reading a recipe and want to cut it in half, or double it, or make one-and-a-half times the amount and everything is going fine until you stumble on dividing fractions. Half of ½ cup is easy, but what is half of ⅓? Well it’s ⅙ of course (to divide fractions you just need to multiply by the reciprocal), but what is that in terms of cups and measuring spoons? It’s really easy if you know the relative proportions of teaspoons to tablespoons and tablespoons to cups. So here is a fun lesson that is messy and memorable:

Then have kids determine the following using the measuring tools:

You get the idea. While I don’t typically adhere to recipes and teach my kids to cook by technique and instinct, there are some great thinking moments in adjusting recipes. This can be made more complicated or simple to make it age/ability appropriate. Ratios Ok, a quick one: I bake by baker's percentages, meaning everything is measured in relation to the flour weight being 100%. No matter how much flour I use, that number is considered 100% and everything else is measured against that 100%. So, if I have 550 grams of flour and want to make bread that is 70% hydration I just multiply 550 by .7 and know that I need 385 grams of water for this loaf. How about 80% hydration (440)? I like to use 3% salt in my bread, so for 550 grams of flour, I simply multiply 550 by .03 and I determine that I need 16.3 grams of salt. Now if I want to make 8 loaves so I can give some to my neighbors, I can have the kids come up with a quick and easy recipe using baker's percentages. This is easily done with a calculator and makes math applicable in the real world and therefore tangible for my kids. It removes the abstract nature of math and answers the question “Are we ever going to use this math in the real world?” There are countless math lessons hidden within the mundane task of preparing meals. Have the young kids count 6 asparagus spears for each family member. Have the older kids learn about budgeting. Stacking functions is the name of the game - we’re making the necessary food, we’re playing and spending time together, and we’re thinking about math in a tangible way. Art and Creativity I bake a lot of sourdough bread. Boules, focaccia, pizza, rolls, croissants, you name it. In order to get my kids interested in eating new vegetables I started making decorative focaccia. It’s amazing to see what the kids can come up with. They get incredibly creative with peppers, kale, potatoes, sweet potatoes, and so on - like in an underwater coral reef scene that all of my daughters put together and then ate! My son especially loves eating edible weeds and flowers - every time he walks under the blooming redbud tree he eats a few flowers. For his 5th birthday he requested candied violets on his birthday cake, so along with a massive amount of Paw Patrol sprinkles he put a bunch of candied flowers on his own cake! If I’m feeling like I need a little head space I encourage them to come up with creative ideas to utilize the weeds in the yard. Just the other day I was pleasantly surprised to see my daughter Clare making an onion and greens soup using mostly ingredients from the yard. She and Jude had that soup for lunch which made my life that much easier and she was so proud of herself! Science If you really want kids to pay attention during homeschool, try out an experiment using chocolate chip cookies! I spent a good part of my career teaching baking and pastry and one of my favorite classes was one where I illustrated universal baking truths using cookies. I had the students make the standard chocolate chip cookie recipe by Ruth Graves Wakefield as the baseline. Then each station was in charge of changing just one ingredient to see what difference it made in the final cookie. Then they were given the opportunity to make their ideal cookie - whether that was crispy, cakey, chewy, brown, or pale - using the baking truths they learned during the experiments. Follow this link for the whole experiment or just take a look these quick tips on how to get started: How to Alter Cookie Recipe (And other baked goods) Want more spread? Use all butter Increase amount of butter Add an extra 1 or 2 tablespoons of liquid (water, milk, or cream. Not egg) Lower acidity of dough by adding an extra pinch of soda Use all-purpose flour Add 1 or 2 tablespoons sugar Bake room temperature dough Want Less Spread? Use shortening instead of butter Decrease amount of fat Replace some liquid with egg Use cake flour (it’s acidic and therefore sets quicker and limits spread) Increase amount of flour Remove 1 or 2 tablespoons sugar Chill dough before baking Want more tender cookies? Use cake flour Add 2 or 3 tablespoons sugar (higher brown to white ratio) Add 2 or 3 tablespoons fat Want less tender cookies? Use bread flour Stir a tablespoon or more of water into the flour before adding the fat and other ingredients Remove a few tablespoons sugar (use a higher white to brown ratio) Remove a few tablespoons fat Want More Color? Use an egg instead of other liquids Use AP flour or Bread flour Substitute 1 or 2 tablespoon of liquid sugar for the granulated sugar Add a bit of baking soda Want less Color? Use water for the liquid Use cake flour Add a touch of vinegar or lemon juice Want to get rid of cracks? Grind sugar in a food processor - the finer the sugar, the less cracking Don’t bake as long Cookies dry out as they age? Use a higher ratio of brown to white sugar (brown sugar attract moisture keeping cookies soft) Add a bit of molasses or honey This experiment not only holds the attention of kids at every age; it can be used to teach the scientific method and illustrate the importance of changing one variable at a time to confidently determine its effect. Not to mention you get a whole bunch of cookies to eat, share, and freeze for the following week when your ice cream is gone and you want to avoid exposing yourself to the germs at the grocery store. Community Building

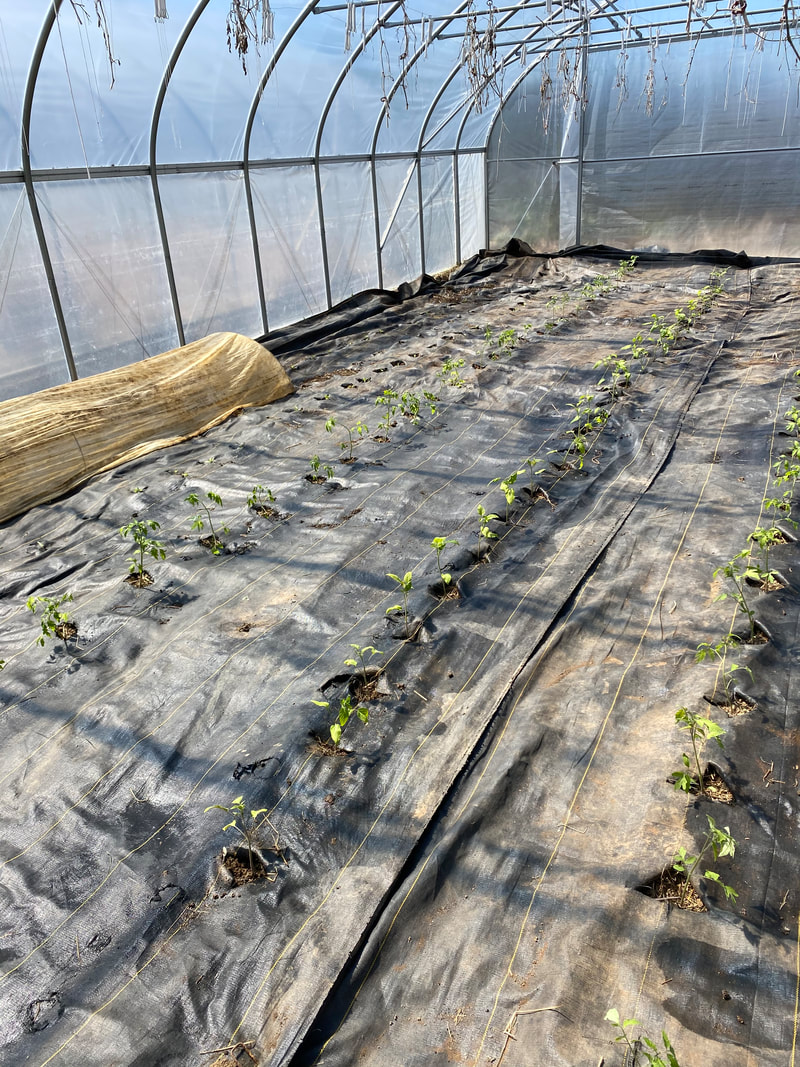

I find community building and citizenship as important as academics and even more so for the younger kids. Building and maintaining a strong community is essential during the best of times and the importance is amplified through this pandemic. Some of the things we’ve been doing include starting a pen pal relationship with our octogenarian neighbor who recently lost her husband and lives alone. This helps in several ways. My daughter Eliza needs to practice her writing, but more importantly I want her to think about how lonely it might be to “shelter in place” when you are all alone. Of course I like to think that receiving the letters brightens our neighbor’s day and perhaps makes her feel less isolated. So how does this fit into the cooking theme? Easy - when I go to the store we ask our neighbors what groceries or other supplies they need and when my neighbors go to the store they do the same for us. When my kids were planning their children’s garden I had them plant extra seeds. So we’ve been able to give away and trade supplies. For example, my brother brings us his fresh eggs and we give him plant starts and root cuttings. We shipped sourdough starter to a friend who can’t find yeast and he taught me how to fix my bike pump so I can continue to ride around the neighborhood with my kids. With skill share, communication, and people care, we’re showing our kids the importance of building and maintaining our community. Expanding The Idea As much as we can, we’re stacking functions, valuing what we already have on hand, sharing the surplus, and making the best of our situation. This is what we’re trying to do in all aspects of our everyday lives while we’re keeping the family out of the danger of crowds. We are nowhere near perfect at this and I need to remind myself that that’s okay. They have fits, full blown meltdowns, and sometimes they struggle to understand why everything is different right now. All I can do is try my best to comfort them and create positive memories so that when they look back on this pandemic, they think of the fun we had. We’re bonding through some difficulties and making the best of our time. Teaching kids can certainly be a handful but there are so many ways to include them, and their lessons, in our everyday lives. Cooking, cleaning, gardening, entertainment, you name it. This is homeschool as opposed to just “school at home.”  Picture This. All hell is breaking loose in the outside world. The stock market has crashed. You’ve been asked to stay home from work. The Governor has cancelled school for the remainder of the year. NBA is cancelled, NCAA is cancelled. You are being asked to stay 10 feet away from people and to remain home unless leaving is absolutely essential. You’ve spent the last week face-timing with friends and homeschooling your kids, and catching up on writing projects while watching the rest of the world descend deeper and deeper into chaos. Nobody has come to visit you because A. you live deep in the country and B. nobody is supposed to visit anybody. Right about then is when I got a visit from a sheriff. Generally speaking, I feel comfortable around law enforcement. Some of this has to do with the structural privilege my intersecting identity brings and the rest has to do with working as a mental health clinician and developing a professional relationship through this experience. Despite this general level of comfort, I am never comfortable when law enforcement pays me a visit. I thought he was bringing shelter in place orders from the Governor on account of the Covid thing. I decided to greet him on the deck, during this national crisis, we don’t want anybody coming into the house that may be a carrier of the virus. I brace for what comes next as the officer gets out of his vehicle and engages me in a conversation respecting the ten foot social distancing norm that has just been established. That’s when he asks me the question. “What are you growing in your high tunnels? I just got one from NRCS and have tomatoes in mine. I’m looking for new ideas on food production and I’ve been driving by your place for years and always wanted to stop by.”  “Now is when you decide to stop by?” I said to myself in my head. I stood quietly, waiting for more. What followed was a long conversation around growing food. And as this happened I began to notice something in his eyes. This man was yearning for connection. Maybe a little worried about the crumbling of the world outside, maybe increasingly feeling isolated due to the current circumstances. I eased into the conversation. It turns out the man is, relatively speaking, a neighbor. Joel Salatin has recently written on Covid that during this time of major upheaval our greatest asset is our immunity. The thought has since struck me that I don’t fully agree with him. I mean, in some sense, he’s right. It’s more of an “and/also” than a “but/instead” disagreement. My thought, not profound but simple is, what if our greatest asset is our network? Sure, immunity brings a sense of security in times of pandemic, and so does a strong network. A couple of decades ago a random visit on a Saturday night by the sheriff would have left me unsettled. These are different times. This one left me feeling more connected to my neighborhood. Maybe that was his goal, or maybe he really is worried about what seems to be a great unraveling in slow-mo. I tucked the thought into my head and went back into the house to work on a Lego project with my kids. The ride’s gonna be bumpy, but we’ll get through it. And my hope is that on the other side, we will all be more connected. Some of ya’ll might still be wondering, what are we doing with our high tunnels? That night we made the decision as a family to change how we are putting our high tunnels to use. What happens next in the economy is up for grabs. Meanwhile, for this summer anyway, we are relatively stable. As a result we have made the decision to develop a by-appointment pick your own style vegetable operation for this season - free of charge. Neighbors, family, and friends will soon fill the high tunnels and the gardens one at a time with their own bags and baskets and leave with nourishing food for their tables. Here is my question for you. What are you going to do to strengthen your network?  I want to write about the economics of teaching permaculture and how it fits into the larger goal of “living in harmony with nature,” which is what permaculture is all about. In the process I’ll probably ramble a bit about economic theory, but I’ll also share specific figures from my 5 years of teaching experience. As a teacher who wants to see permaculture grow, I think it is important to be open about how and why we teach courses. I’ve been interested in economics as a lense through which to view human interactions with the planet for a long time - and I’ve zigzagged all over the political spectrum. In 7th grade I got seduced by Ayn Rand libertarianism, in high school I rejected capitalism and started reading the Monthly Review, and in college I “saw the light” in liberal economics and the technocratic effort to utilize capitalism for its benefits (efficient allocation of resources) while regulating its negative externalities (pollution, income inequality, etc.). Then, in my mid-twenties, like a lot of millennials, I got jazzed on the idea of socially-responsible entrepreneurship and the triple bottom line (we can have our money and feel good about it too!). In the past few years, as I’ve gotten married, racked up medical debt, bought land, and had a baby, my main focus has shifted to building economic stability for my family. I’ve been forced to accept, for better and for worse, our current economic context and figure out how to create resiliency within it. That means I get stoked about things like health insurance and matching retirement funds instead of the ideas of Keynes and Hayek. Don’t get me wrong, I am still interested in designing a path towards a better system, it’s just that my priorities have shifted - call me a realist with big dreams. Enter permaculture design and the side hustle of teaching… I got into permaculture to learn how to design thriving human habitats that increase the health of the planet. At age 25, a few years out of college, I spent $1,200 to get my Permaculture Design Certificate. Compared to the cost of my undergraduate degree it was a small educational investment, although it was about half of my savings at the time. That investment launched my permaculture journey and a few years later I found myself as a teaching apprentice. At that point the only motivation to teach was Bill Mollison’s directive of “each one, teach one” - to spread the gospel that I thought could save the world. Fast forward another few years and I now co-own a permaculture education business along with Emilie Tweardy and Ryan Blosser. The teaching impetus is still the same, but now I have to make a certain amount per course to pay the business expenses and to justify spending time doing the work instead of being at home with the family. Here is a little breakdown of the finances for the average SPI PDC, to put things into context: Revenue Cost Per Student: $1000 # of Students: 15 Course Revenue: $15,000 Expenses: Administration overhead ((taxes, licensing, insurance, accounting) - $2,250 Guest Teacher Fees: $2,500 Teacher Apprentice Fee: $200 Supplies and Food: $500 Space Rental: Donated by SPI Teaching Team Course Coordinator Fee - 18% revenue: $2,700 Total Expenses: $8,150 Lead Teacher Hours: Prep Hours: 50 Teaching Hours: 90 Profit Course Profit: $6,850 Take-Home Profit Per Lead Teacher: $2,283 Average Hourly Wage Per Lead Teacher (before taxes) = $16.28 As you can see, I make about $2,000 per course once you factor in income and self-employment taxes, and each course is a 4-weekend commitment, plus planning time. If we teach 2 courses in a year that is about $4,000 in supplemental income for my family - not an insignificant amount but also not exactly a game changer. This works for us right now, but I know that if I were to make much less I couldn’t justify it, even though I love doing it. So there it is, our current money-based financial teaching model. Obviously, there are pros and cons to this model. What I like about it is that the monetary model incentivizes teachers to work hard, be accountable and professional, and provide a good product. It also provides clear feedback in the form of enrollment numbers - if we aren’t serving our customers we will find out quickly. Incentivizing people to work hard is one of the biggest benefits of the market mechanism from my experience, especially in team projects - have you ever worked with a group of unpaid volunteers and tried to get action items completed thoroughly and on time? There are also some things I don’t like about our model, the biggest one being inaccessibility. Afterall, only a certain percentage of people are in a position where they can spend $1,000 and 4 weekends on a class. The other drawback to the monetary model is that it can be tempting for a teacher to pump out courses just to make cash. I never want to get so wrapped up in the lucrativeness of teaching that I stop doing the actual work of permaculture - developing my farm and building my community in harmony with nature. There are certainly other models for teaching out there and we have and will continue to explore them. We could teach informal free courses and avoid all of the costs of licensing, taxes, accounting, etc. We could go digital like Geoff Lawton, drastically decreasing our overhead and tuition while reaching more students. Both options would decrease the quality of our courses in different ways. We could also start taking other forms of capital as payment for our courses (see Ryan’s blog series on Time Banks and the 8 Forms of Capital). We’ve tried scholarships and a sliding-scale, but we’ve found that neither is an effective way of making the course accessible to students in true financial need. It’s so difficult to come up with a way to measure need that we’ve found no significant difference in socioeconomic position between our students who take advantage of the tuition discounts and those who don’t. So, for now, we’ve settled for an early bird discount and the option of a tuition payment plan as ways of helping those with limited financial resources. Our current model isn’t perfect, but it is working as a way to spread the powerful and much-needed idea of permaculture. And that’s the key for me: it has to work, or else we’re not doing anyone any good. So, for now, we utilize this tool called money while keeping our greater goals in mind, moving forward, and always being open to feedback and change.  My colleague Ryan asked me to write a blog about swales - actually, he asked me to write a blog about “why swales aren’t necessary and why we should all stop doing them except in clear cases where the design calls for it based on functional need.” Oh, and by the way, Ryan has a half-acre of ridiculous hand dug swales in his food forest - and me, I’ve left a trail of annoying swales over every project I’ve worked on….so here it goes! My basic contention is that in the Mid-Atlantic climate swales are very rarely necessary, especially given how drastic, costly, and permanent they are. From a design perspective, we should be asking ourselves, “What is the problem or opportunity I am trying to address and what is the most appropriate and efficient way to address it?” We should not be asking ourselves, “Where should I put the swales?!” Unfortunately, that’s still a question I hear all the time, including in my own head. It’s actually really weird that we are all so obsessed with swales when you think about it. After all, they are basically giant, expensive scars on the earth that make mowing a real pain in the ass. Maybe it’s Geoff Lawton’s fault for pumping us all with heady before and after images of lush, fruit-filled swales in the Australian tropics, all with a charismatic twinkle in his eye. Whatever the reason, the idea of swales has attached itself to the zeitgeist of permaculture like a bunch of burdock burs, planting itself around the world in the process. So back to design…The main function of a swale is to slow down water sheeting across the landscape and infiltrate it into the soil, making it available to plants when otherwise it would be lost. So when might we want to utilize that function in design? The most common use of swales is in an orchard setting. Here’s the problem - most temperate climate fruit-trees (apples, peaches, cherries) are adapted to semi-arid regions and do not actually require that much water. The 3 inches per month average that we get in the Mid-Atlantic is plenty for most fruit trees once they’re established. What’s more, for some trees like apples, too much water can make them too vigorous, leading to an abundance of vegetative growth at the expense of fruit. There is one big benefit to swales for fruit trees - they provide a raised-bed that will drain and dry out after heavy rain (fruit trees like to be inundated with water periodically but not stay wet). So if your soil doesn’t drain you could theoretically dig some swales and plant on the berms to achieve better drainage. The problem here is you are not actually solving the underlying problem - you still have that compaction layer below your swales. A cheaper and more effective intervention might be ripping your landscape with a sub-soiler or Yeoman’s Plow on a keyline pattern to simultaneously de-compact, redistribute water, and build soil. So swales in a Mid-Atlantic orchard? Probably not. The reason Geoff Lawton uses them in Australia is because he is growing water-hungry plants in an arid environment that gets huge sporadic rainstorms. When he gets rain he wants to capture every bit of it for his parched system. So when might swales be appropriate in the Mid-Atlantic? One instance might be in a no-till, non-irrigated vegetable garden. Veggies need a lot of water, and when designed right and combined with deep mulch this system could enable you to grow veggies without any supplemental irrigation. Michael Judd has utilized these types of swales beautifully in his work at Ecologia Design. Another example might be a steep, compacted site with heavy clay soil where subsoiling is inaccessible or impractical. Alternately, I sometimes use swales on a 1% grade to slowly move water off of my site, for example, to get it away from the foundation of a house. Lastly, swales might help for growing water-loving plants like Paw Paws, especially if you can get multiple functions out of them (see Emilie’s Blog “Stacking Functions Part 1 - Paw Paw Perfection”). When Ryan asked me to write this blog he suggested 500 words or less. But now that I’ve written well over 500 words, I’ve realized the subject is actually a bit complicated. I guess that’s because swales, just like good design, are all about your goals, your context, and the unique and evolving characteristics of your site. Turtles All The Way Down. The Third Installment Of An Exploration Of Permaculture Economics.  I’m on the home stretch of thinking out loud about time banking and folding the thoughts into a larger understanding of how we approach economics in Permaculture. At the end of this, I hope to have a clearer opinion of time banks myself and to have communicated to you deeper understanding of how this tool fits into our permaculture toolkit as designers. First, I want to tell a story and introduce an idea. They may not connect yet, hang in there. The final installment will bring it all together. There I was, standing in my driveway, untangling my headphones before a run when I noticed a late model minivan speeding down the road. Just as the van reached my driveway, the window rolled down and out came flying a fast food bag filled with empty wrappers and red bull cans. As the minivan sped away, two things stood out. The driver’s bright colored Patagonia windbreaker and an "I Love Mountains" bumper sticker. My area of the road collects a lot of trash. I think it’s due to the fact that 3.5 miles away is a convenient store and Tastee Freeze. It takes about five minutes to reach this point which is, by my best observational research, the perfect amount of time to inhale a chili dog and slam a red bull. On the run following this event, I had many thoughts. I thought about taking a picture of the van and posting it to social media. Participating in the current online call-out culture by metaphorically throwing the driver into the online public square for all to feast on her sins. Next, I thought about one of my heroes, Edward Abbey, whose complicated brand of iconoclastic environmentalism included the occasional and purposeful chucking of an empty beer can out of the window. Maybe our driver read Edward Abbey. Maybe that’s why she loves mountains. The next thought that flashed through my head was a statistic I read the other day about Charlottesville, VA. (It must have been the Patagonia jacket that caused that association.) Charlottesville is known in our region as a progressive enclave, lauded for their green living aesthetic. Indeed I have conversed with many an environmental champion from Charlottesville. However, the statistic that struck me as confusing and interesting was that the average household in Charlottesville, VA. produces a ton - that’s right - a ton more carbon emissions per household than the average in the United States. This thought did not help my mood. Linked is a thoughtful piece on this https://www.c-ville.com/weve-got-work-to-do-lagging-behind-charlottesville-aims-for-more-ambitious-climate-goals/ Just as my self-righteous fury was working itself into a frothy towering Gandalf-style shaming, I thought about all of the plastic I’ve used as an organic farmer. Did I mention I’m an organic farmer (queue condescending west coast accent hippy voice.) When it comes to the “I’m greener than you” fronting on social media that takes place surely I've got that title on lock-down. Nope. The amount of plastic I use is sickening. At one point last season, while investing in a new piece of land I had just opened up, I was spending upwards of a thousand dollars a week for a couple of weeks straight on plastic that would be tossed in just a few seasons. And to think, y’all worry about straws. Every time you bought my beautiful organic produce, you supported my plastic habit. Setting limits is a good thing. But this is not a blog about that. Rather, these words are about perspective. Rather than invite you to judge anyone of the people and communities I have written about, I’d like to invite you to think about yourself. Now put a pin in that, while I introduce an idea. We will come back to that thought later. In our Permaculture courses, we teach the 8 forms of capital. It’s a brilliant conceptual framework for thinking about economics. For an introductory understanding of this concept check out Ethan Rowland's original article at the following link. Dude is a crystal clear thinker and this concept has contributed in a big way to the conversation about economics in Permaculture. http://www.appleseedpermaculture.com/8-forms-of-capital/ In thinking about economics he expanded the understanding of capital beyond finance into other realms. His 8 forms are as follows. Financial Social Living Intellectual Experiential Cultural Spiritual Material It never fails. Whenever we teach this, folks always feel drawn towards value judgments about which form of capital is superior to the other. Often financial capital gets put at the bottom and social capital gets placed at the top of the pile. This, I believe, misses the point. Don’t get me wrong, I get it. Social capital is the feel good one and some permaculture practitioners in all of our upper-middle-class wisdom like to demonize and discount the importance of financial capital. In Rowland's conceptual framework he does a nice job of exploring how each form of capital has the potential for deficits and credit and that this creates opportunities. The brilliance of the 8 forms of capital is that it is a tool for analysis and for design. Much like the way we use the scale of permanence, we now have a tool to analyze our economic landscape and create informed decision trees for how to intervene. Decisions have consequences. With the run over, I climbed out of my head and found myself standing in the driveway again. There was a fast food bag still littering my space. I walked over and picked up the lady’s shit. I wasn’t angry. I was happy to do it. Serene almost. Somebody somewhere is cleaning up my shit. We’re all cleaning up Charlottesville’s shit. There’s no such thing as a free lunch. It’s turtles all the way down. |

Authors

Daniel Firth Griffith Archives

June 2022

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed